Hackers can kill Diabetics with Insulin Pumps from a half mile away - Um, no. Facts vs. Journalistic Fear mongering

UPDATE: Jay Radcliffe, the researcher discussed in this post, has emailed me, a little upset. In the interest of transparency I've included our email thread at the end of this post so that Jay's perspective on any inaccuracies may be seen. I encourage you to draw your own conclusions.

There's a story making the rounds on Twitter right now. Engadget "reports" researcher sees security issue with wireless insulin pumps, hackers could cause lethal doses.

Wait till you see what researcher and diabetic Jay Radcliffe cooked up for the Black Hat Technical Security Conference. Radcliffe figures an attacker could hack an insulin pump connected to a wireless glucose monitor and deliver lethal doses of the sugar-regulating hormone.

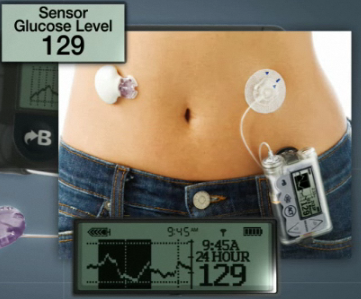

First, a little on my background. I've been Type 1 diabetic for 17 years. I've worn an insulin pump 24 hours a day, 7 days a week for over 11 years and a continuous glucose meter non-stop for over 5 years. I also wrote one of the first portable glucoses management systems for the original PalmPilot over 10 years ago and successfully sold it to a health management company. (Archive.org link) I also interfaced it (albeit with wires) to a number of portable glucose meters, also a first.

Engadget's is a mostly reasonable headline and accurate explanation as they say he "figures an attacker could..." However, Computerworld really goes all out with the scare tactics with Black Hat: Lethal Hack and wireless attack on insulin pumps to kill people.

Like something straight out of science fiction, an attacker with a powerful antenna could be up to a half mile away from a victim yet launch a wireless hack to remotely control an insulin pump and potentially kill the victim.

The only thing that saves this initial paragraph is "potentially." The link that is getting the most Tweets is VentureBeat's "Excuse me while I turn off your insulin pump," a blog post that is rife with inaccuracies (not to mention a lot of misspellings). Here's just a few.

- "Insulin pumps use wireless sensors that detect blood sugar levels and then communicate the data to a screen on the insulin pump."

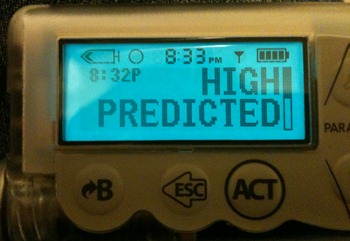

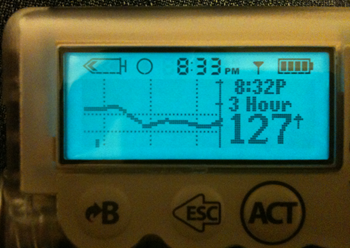

- Way too broad. Pumps don't. Some CGMs (continuous glucose meters) communicate with special integrated pumps. The most popular integrated system is a Medtronic Paradigm. Most other CGM system have a separate "screen" device that's separate from the pump.

- "The sensor has to run on a 1.5-volt watch battery for two years."

Nope. The Medtronic receiving sensor needs to be charged ever 3 to 6 days. The pump battery is usually a AAA that lasts a few weeks.

UPDATE: The Dexcom receiver is recharged every 3 days but the body transmitter is warrented for a year with a small watch battery.

One useful paragraph in the VentureBeat post points out again that Jerome wasn't able to decode the message. Here, emphasis mine.

Then Radcliffe went through the process of deciphering what the wireless transmissions meant. These transmissions are not encrypted, since the devices have to be really cheap. The tranmissions [sic] are only 76 bits and they travel at more than 8,000 bits per second. To review the signal, Radcliffe captured the signal with a $10 radio frequency circuit board and then used an oscilloscope to analzye [sic] the bits.

He captured two 9-millisecond transmissions that were five minutes apart. But they came out looking like gibberish. He caputred [sic] more transmissions. About 80 percent of the transmissions had some of the same bits. He reached out to Texas Instruments for help but didn’t have much luck. He told the TI people what he was doing and they decided not to help him.

That was as far as he got on deciphering the wireless signal from the sensor, since there was no documentation that really helped him there. He couldn’t understand what the signal said, but he didn’t need to do that. So he tried to jam the signals to see if he could stop the transmitter. With a quarter of a mile, he figured out he could indeed mess up the transmitter via a denial of service attack, or flooding it with false data.

Now, to the security issue. One has to read these articles and blog posts very carefully. It's easy Link Bait to say "A hacker can kill diabetics wirelessly without them knowing it!" (I assume we'd figure it out at some point, though.) While Jerome Radcliffe, the gentleman who did the proof of concept, is no doubt very clever, the folks who are blogging this fear mongering should do their homework and read the details. Jerome is presenting some of his findings at the BlackHat conference. Here's his abstract with emphasis mine. Note also that SCADA means "supervisory control and data acquisition." He's saying that we "cyborgdiabetics" (my term) are human control and data acquisition systems as data-in/control-out controls our health, well-being and ultimately our lives.

Now, to the security issue. One has to read these articles and blog posts very carefully. It's easy Link Bait to say "A hacker can kill diabetics wirelessly without them knowing it!" (I assume we'd figure it out at some point, though.) While Jerome Radcliffe, the gentleman who did the proof of concept, is no doubt very clever, the folks who are blogging this fear mongering should do their homework and read the details. Jerome is presenting some of his findings at the BlackHat conference. Here's his abstract with emphasis mine. Note also that SCADA means "supervisory control and data acquisition." He's saying that we "cyborgdiabetics" (my term) are human control and data acquisition systems as data-in/control-out controls our health, well-being and ultimately our lives.

As a diabetic, I have two devices attached to me at all times; an insulin pump and a continuous glucose monitor. This combination of devices turns me into a Human SCADA system; in fact, much of the hardware used in these devices are also used in Industrial SCADA equipment. I was inspired to attempt to hack these medical devices after a presentation on hardware hacking at DEF CON in 2009. Both of the systems have proprietary wireless communication methods.

Could their communication methods be reverse engineered? Could a device be created to perform injection attacks? Manipulation of a diabetic's insulin, directly or indirectly, could result in significant health risks and even death. My weapons in the battle: Arduino, Ham Radios, Bus Pirate, Oscilloscope, Soldering Iron, and a hacker's intuition.

After investing months of spare time and an immense amount of caffeine, I have not accomplished my mission. The journey, however, has been an immeasurable learning experience - from propriety protocols to hardware interfacing-and I will focus on the ups and downs of this project, including the technical issues, the lessons learned, and information discovered, in this presentation "Breaking the Human SCADA System."

Just to be clear, Jerome has not yet successfully wirelessly hacked an insulin pump.

UPDATE: See below email thread. Jerome says he can change settings and pause the pump. This may be via the USB wireless interface one uses to backup settings and send their blood sugar to their doctor. That's an educated guess on my part.

He's made initial steps to sniff wireless traffic from the pump. I realize, as I hope you do, that his abstract isn't complete. Hopefully a more complete presentation is forthcoming. I suspect he's exploiting the remote control feature of a pump. This is a key fob that looks like a car alarm beeper that some pump users use to discretely give themselves insulin doses. However, I feel the need to point out as a pump wearer myself that:

- Not every Insulin Pump has a remote control feature.

- Not every remote-controllable insulin pump has that feature turned on. Mine does not, for example.

In this AP article reposted at NPR called Insulin Pumps, Monitors Vulnerable To Hacking they give us more of the puzzle which confirms that Jerome was - in at least one hack attempt - using the optional remote control feature of the pump. A feature that few turn on. Their tech is a little off as well with talk of a 'USB device,' probably an Arduino with an RF shield.

Radcliffe wears an insulin pump that can be used with a special remote control to administer insulin. He found that the pump can be reprogrammed to respond to a stranger's remote. All he needed was a USB device that can be easily obtained from eBay or medical supply companies. Radcliffe also applied his skill for eavesdropping on computer traffic. By looking at the data being transmitted from the computer with the USB device to the insulin pump, he could instruct the USB device to tell the pump what to do.

Finally, another piece of the puzzle is found at SCMagazine's scary "Black Hat: Insulin pumps can be hacked" article where they open with:

Finally, another piece of the puzzle is found at SCMagazine's scary "Black Hat: Insulin pumps can be hacked" article where they open with:

"A Type 1 diabetic said Thursday that hackers can remotely change his insulin pump to levels that could kill him."

ZOMG! Someone can remotely control my insulin pump? They continue...

"Radcliffe, now 33, explained that all he requires to perpetrate the hack is the target pump's serial number."

Oh, you mean the serial number that I use to pair with the transmitter to use the highly touted remote control function? This is like saying "I can open your garage door with a 3rd party garage door opener. Just give me the numbers off the side of your unit..."

What Jerome has done, however, is posed a valid question and opened a door that all techie diabetics knew was open. It is however, an obvious question for any connected device. Anyone who has ever seen OnStar start a car remotely knows that there's a possibility that a bad guy could do the same thing.

For example, literally last month I personally exchanged emails with a friendly hacker who successfully hacked the web services for the Filtrete Touchscreen WiFi-enabled Thermostat. Harmless? Perhaps, but his hack could successfully remotely control a furnace or AC in the house of anyone with this device. Any control device that's connected to the "web" or even "the air," in the case of insulin pumps, is potentially open for attack.

I appreciate the message that Jerome is trying to get out there. Wireless medical devices need to be designed with security in mind. I don't appreciate blogs and "news" organizations inaccurately scaring folks into thinking this is a credible threat.

We don't know what brand pump was experimented on, and fortunately the gentleman isn't giving away the technical details. If you are a diabetic on a pump who is concerned about this kind of thing, my suggestion is to turn off your pump's remote control feature (which is likely off anyway) and turn off your sensor radio when you are not wearing your CGM. Most of all, don't panic. Call the manufacturer and express your concern. In my experience, pump manufacturers do not mess around with this stuff. I'm not overly concerned.

All this said, I'd love to have him on my podcast. If you're reading this and you're Jerome Radcliffe, give me a holler and let's talk tech.

Of course, all this talk would be moot if we cured diabetes. In encourage you to give a Tax Deductable Donation to the American Diabetes association: http://hanselman.com/fightdiabetes/donate

Also, feel free to show people my "I am Diabetic. Here's how it works" educational video on YouTube with details on how I setup a pump and continuous glucose monitoring system every 3 days. http://hnsl.mn/iamdiabetic takes you right to the YouTube video.

UPDATE: In the interest in full disclosure, here is my email thread with Jay. As I've said, I'm happy to update the article, as am I doing here, with all perspectives. This was as much a blog post about the media and that meta-point as it was about the tech. Given that I had to piece this post together from several other posts and articles just to get an idea of what the big picture is, kind of makes my point about the problems of hyperbole in the media. Again, my concern is more about sensationalism than it is about the tech. I have no doubt a pump CAN be hacked. Any connected device can be hacked.

Here's our thread from earliest to latest:

From: Jerome Radcliffe

I *can* hack an insulin pump. I can suspend it, change all the settings remotely. I did that on stage. I'm quite disappointed that you did not verify any of the information in your article. People do die from hypoglycemia. Is it an extreme example? Yes. It needs to be. These devices need to be researched for security flaws. To talk about why someone might hack a pump misses the point.

From: Scott Hanselman

I'm sorry, I only found the articles I linked to, plus the abstract that said you hadn't. I tried to verify everything to the best of my ability to Google. Would you send me some newer links and I'llr update my post? My post was meant as an analysis of the news coverage more than the attack. Send me new info?

Thanks!

From: Jerome Radcliffe

I understand your position. but as a blogger/journalist there is a certain level of responsibility to publishing facts. You come off as hypocritical blaming the media for being inaccurate on diabetics being killed by pumps, and write a piece riddled with inaccuracies on my research.

1. There is a CGM that runs on a 1.5v battery for two years. You state that my research is wrong. It is not.

2. Check CBS in las Vegas's web site. They have a video of the demo. Several media outlets reported that demo.

My name is fairly unique and my email address is easy to acquire. I would have rather you contact me for clarification rather then publish a critique of my research that is far from accurate.

From: Scott Hanselman

A random blogger and a trained journalist are certainly different things, I'm sure we can agree on. I do certainly want to improve the post and add the facts and am more than happy to do so.

I'm not sure where I said "your research is wrong" in my post, but I will re-check it. Again, most of my post is quotes from actual journalists who presumably interviewed you and I quoted them. I also quoted your black hat abstract.

I searched twitter for Jay and Jerome Radcliffe but didn't find you and wasn't able to find your blog, I suppose because of the flood of new links and stories.

This CGM runs for 2 years without recharging? Perhaps I'm confused about semantics. I've had a number of CGMs, some 1.5V and all the ones with embedded batteries needed recharging. I'll check around. Again, however, my assertion wasn't against you at all, rather the journalists whose stories were inaccurate.

I feel like we are getting off on the wrong foot here. I thought I wrote a post about how other journalists and bloggers were sensationalistic and inaccurate in their coverage. My post isn't meant as, nor should it read as, a personal attack on your hard work. As I said earlier, I'm more than happy to make updates and edits and fall on my sword with any inaccuracies. I'm even happy to post our email exchange.

Be well!

From: Jerome Radcliffe

Anytime you publish, blog or newspaper, you should be responsible for the content. There is no difference between a trained journalist and a blogger. You can't duck your own criticism of responsible reporting because you feel like your [sic] just a random blogger. The fact you are so critical of my work, you have been getting a lot of press. Your article was in the Slashdot headline, which is one of the most popular sites on the Internet. The fact is your article was highly critical of my work, and highly inaccurate. Even after I specifically told you about the inaccuracies in your writing you have not corrected them.

It's really hard for me not to be offended in this case. For the last three days I have had to answer people's questions, many have cited your article based from the Slashdot coverage.

Related Links

- Details on the 2010 Diabetes Walk and a Thank You

- Diabetes: The Airplane Analogy

- A Diabetic Product Review for Non-Diabetics - The Medtronic MiniMed Paradigm "Revel" Insulin Pump and CGM

- New integrated real-time glucose meter and pump coming THIS SUMMER

- Technology and the first insulin pump...

- Diabetics and Travelling Time Zones

- CNN: Scientists work to keep hackers out of implanted medical devices

About Scott

Scott Hanselman is a former professor, former Chief Architect in finance, now speaker, consultant, father, diabetic, and Microsoft employee. He is a failed stand-up comic, a cornrower, and a book author.

About Newsletter

At least I can take a few days off from my routine here and there without consequence, but you have been doing this now for 17 years. I never really knew how much your life revolves around taking you blood sugar. I guess that is why you said to eat foods that are consistent and predictable like your favorite Subway sandwich. I donate to National Kidney Foundation, but I think this year I’ll be spreading it out. Great article Scott!

Sorry if this comment shows up more than once. I had trouble logging in with my OpenID.

This is all I could find.

http://forecast.diabetes.org/news/nz-researchers-implant-pig-cells-diabetics

http://www.stuff.co.nz/southland-times/news/5233590/Pig-cell-trial-improves-diabetic-mans-sight

Thanks for the clarification. I am amused however that you never touched upon one key aspect.

MOTIVE. Why would someone want to kill a diabetic? By the time someone really important got

ill, not only would we have got more secure and reliable tech, we would probably have found a cure!

That is just my opinion. Maybe hackers working with the software developers can develop global Diabetics monitoring to create some form of grisly social network for diabetics or allow for medicalpeople quickly get to people in distress. The uses for "hacking" insulin pumps are myriad. in fact, I have just now been inspired to develop an app for windows phone 7!!

What I am trying to say here is, we should not only look at the morbid and unlikely aspect alone but alsolook at the positive ones ;-)

Look after yourself Scott.

Every year, a few stories make their way to the mainstream press from Blackhat, and they always end up pale shadows of the actual content of the talks. The usefulness of the research ends up getting mired in the sensationalism that inevitably ends up swallowing the story.

As a rule, folks in the security industry don't give a lot of credence to the reporting of stories associated with security (which over the years has caused me to wonder if other professions see stories in the press about what they do and are likewise horrified).

There's a lot of interesting work going on now in non-traditional systems security. A lot of it started a few years back with network equipment (consumer grade routers and so forth), and it would seem to be an area of growing concern as more and more things get connected. For various reasons, SCADA is currently a hot topic (as is APT, but that's a whole nother rant.)

One of the scariest things I ever saw was doing a penetration test of a patient monitoring system in the ICU of a hospital where the systems were reachable from the internet (as in, not NAT'd, and no access restrictions). To make things worse, there were no other computers in the ICU, so the nurses used the systems to check their email and surf the web. I was terrified.

One thing is not clear to me from your educational video - why do you change your insulin every 3 days (meaning you load your reservoir with 90 units of the maximum 300)?

I am using the same pump and while I change the infusion site every 2 days, I have a full reservoir of insulin which lasts me about 6.5 days (I use average of 45 units, 28 basal and 17 bolus, which is another concern of mine -- how does your body manage with just 30 units, i.e. only 66% of my own insulin requirements, which I thought, until now, are pretty good).

One possibility I'd guess is that you want fresher and thus more active insulin, but according to med stats insulin is supposed to last in room temperature up to 4 weeks.

Greets,

Stanislav (fellow type I and developer)

As for how I manage on 30U? That depends on a number of things. How big are you? Bigger people need more insulin. I'm 5'11" and I weight 172lbs. I've recently lost over 20lbs, which has taken my daily insulin down from 45-50 to 30U. I'm also very low carb and I work out. Each of these things lowers daily total insulin more and more. Also I take (sometimes) Victoza and Symlin which I am sure can help. When I'm really fit and really eating low carb I've had 17U days. TOTAL.

Robert - Of course that's me in the picture, can't you tell by my lady hips? ;)

Thought this meant be of interest http://www.marksdailyapple.com/primal-blueprint-success-story-former-marathoner-beating-diabetes/

/Cal

It might be worthwile to point out that the pump doesn't give its insulin silently, the Animas my son uses gives a couple of vibrates (like your phone) before it starts delivering boluses (larger insulin amounts, what you'd use to kill I presume). When the pump wearer is awake, they'd know something's going on.

Let's hope this kind of nonsense doesn't slow down development/approval of closed loop devices, where the CGM does remotely control the pump, e.g. by shutting off insulin when it detects a low blood sugar.

There are three devices that could potentially have some effect on my pump (yes, I'm a pump user, have been for 10 years). There is the little remote, the CGMS sensor transmitter, and then the USB dongly thingy that the use to upload the data to the web site so they can draw pretty graphs (and my Doctor probably uses something similar).

Now, of these three, the CGMS doesn't pose any real risk...the worst that can happen is I get crappy (or no) CGMS data. The little remote is potentially bad because it can be used to both suspend the pump, and deliver insulin. But in order to do that it has both be enabled, and then the serial number of the remote needs to be input on my pump. So if it is disabled, no problemo, if not a potential attacker would need to know what the serial number was of the device I had configured. If that happened, and if they were within range they could tell my pump to deliver some deadly amount of insulin. But when the remote is used the pump will beep (or vibrate) for every step up (you don't put in an amount, you basically click an "up" button until you get the amount you want), and then beep (or vibrate) again when it starts delivery (which I can stop at any time). The same goes for suspending the pump, it beeps at me when I do it. Not only that but it beeps at me every 15 minutes while it's suspended (so bone-heads like me don't forget to start it up again). I don't really see a way someone could do this without me knowing.

Now, for the USB dongly-thingy...It can suspend the pump and transfer data, assuming the "attacker" has the serial number of my pump. If someone got my serial number they could suspend my pump which would (all together now) beep at me when it happened, and then beep at me again every 15 minutes until I start it up again.

I can't speak for anyone else for sure, but I have a feeling that anyone with an insulin pump has super-batman hearing when it comes to the beeping noises your pump makes. As a matter of fact when I'm listening to one of the podcasts Scott does and his pump beeps, I automatically check mine. Even if these things did happen I would be on the phone with the manufacturer, and more likely than not be getting a new pump in the mail overnight because mine is suspending itself mysteriously.

The one thing that could potentially be scary here is if the manufacturers left in some secret back-door codes that you could use regardless of what you have setup in your pump (kinda like the Microsoft activation keys in the late 90s), then there would be less barrier to someone being able to do something bad. Even then, though, I would still be a slave to the beeping, and would find it unlikely that anyone could do anything bad without me being able to immediately undo whatever bad thing they did.

Awesome article. I have relatives who have been freaking out about this possibility and my answers have been mostly, "No actual exploits are known, any networked device is potentially vulnerable." Now that you have a much nicer explanation with technical details that I never knew about, I have an article to refute the dumb internet articles I get sent with questions. Anyone who debunks scare mongering is good in my book, thanks man!

I think that even if a method to attack one of these remotely was found, the risk would be rather small in most cases. Turning the machine off or making it stop giving insulin would likely be caught by the diabetic before any serious risk was involved. In my experience diabetics on pumps carry backup insulin and injection needles... for backup.

I would imagine the larger risk is giving a dose that is way to high, which will also be caught by the diabetic in pretty much every case, and more than likely in time to get help or take some glucose tablets/glucagon.

To be truly lethal I think the dose would have to be crazy high and given in a very short amount of time, which these machines simply won't do. They are crazy expensive, partly because of all the rigorous safety and validation testing they must go through, the motors inside of them are designed to the highest industrial precision to give out tiny, but extremely accurate doses of insulin. I have a very hard time imagining there is any significant risk to the diabetic at all.

The risk would be much higher in a new diabetic / very young, who was not well acclimated to their new diabetic status and would have a harder time noticing the warning signs. But again, from what I understand, these pumps are rarely if ever given to someone in those circumstances.

I was wondering how much leeway does the pump + shots give you regarding diet? Can you indulge in a milkshake once in a while or is that like playing Evel Knievel?

-- Robert

Robert - My one splurge is a 300 calorie Mini Blizzard from DQ. Maybe twice a month. It's a bit of a rollercoaster but it's manageable if it's a rare thing.

Most of us relying on these medical devices have been assuming that they were secure. Not just barely secure enough so that we can't be killed by someone who doesn't know what he's doing, but really secure.

If it was necessary to acquire the serial number to the device in order to hack it, then that's a simple enough thing to do. Heard of phishing? Dumpster diving? Someone with a specific target in mind, someone they knew, could probably innocently get a look at their unwanted relative's insulin pump or CGM.

Someone without a specific target could simply extrapolate from one or two serial number what range many other serial numbers might be in, and broadcast in locations where diabetics (or users of pacemakers or whatever) congregate.

If I were a famous diabetic, using a known brand of pump, like Nick Jonas, Crystal Bowersox, or Team Type 1, I would be seriously concerned about this.

I think Jay Radcliffe's intent was to get medical device companies to get serious about security. If we act like this is no big deal, if we don't insist that security is improved on these things, then he failed.

- openness - One thing that I would love to see more of out of these devices is an open data protocol so that geeks like us can look produce more interesting data analysis applications than those provided by the vendor of the device. Their primary interest is in selling the device and will do the absolute minimum in producing useful software to maintain sales. Geeky consumers on the other hand are primarily concerned with better control. The massive amount of data in the CGM combined with the pump data and some external inputs for things like exercise could be much better analyzed than they are today. (I am thinking an awesome use of the Solver Framework :) )

- security - I do get that the communications on these devices should be secured to some degree. I am afraid that the vendors will use that as a way to further lock down the access to the important information inside. There is a big difference between viewing the data and controlling the device

-discovery - I think the work that Jay Radcliffe did was important. I think letting the vendors know ahead of time is important

- sensationalism - I think the delivery and the media coverage is way over the top. This seems like a good idea implemented in entirely the wrong way

This cracks me up. I'm a Systems Admin and a T1 Diabetic. Any electrical sound, be it a beep or HDD Actuator Arm skipping makes me peek with curiosity. I've worn a Minimed Insulin Pump for the last 10 years and am well used to the triple beep alarm that my pump is turned off. I think any Diabetic with a pump jumps at the tone of one of the familiar warning beeps.

More Diabetic speak: I take an average of 10u bolus a day. I think if I was dolled out 20u by way of hack, it would be one horrid day, but correctable. That is unless my Dexcom was DOSed, my (3) meters failed, and my LBS sensitivity was gone. All unlikely to happen at once. I think most of us pay way to close attention to our BGs and CGM trends to not notice and catch something like a 20u bolus. Still, even if we didn't, it would only bring about a day of LBS combating.

This, I find, to be a very interesting point about the presentation of all this. I'm not smart enough to know whether anything he presented was technically accurate or not, and have not been able to find the video of it. But as someone outside of this industry, the above point about responsible-disclosure.

Instead it's... someone ticked off for being called out? ;/

Jay: Instead of complaining and saying stuff is inaccurate, why don't you actually give a detailed explanation of what is inaccurate and why.

Disclaimer: Software Engineer and Type 1 Diabetic pump user. All this stuff seems pretty far fetched and extremely unlikely to me so far.

In general I find all of this hacking to be fairly pedestrian. Maybe that is why Jay picked a target that he knew would make headlines.

Unfortunately that is the way change occurs at most company levels, in response to customer demand, especially when additional expenses are involved. We all hate the sensationalist fear-machine that our media has become, sometimes for things it has totally wrong and sometimes (like now) for legitimate issues; you yourself say that he is highlighting the fact there is a lack of security around these devices. Although we don't agree with the degree that the media has taken it ("everybody will die!"), it forces perception change on the masses which translates to change at the companies.

If there was no fear mongering then the story would probably still be out there on the Internet with little to no coverage, and nothing would be done by the companies to change it. That should NOT be the way it works, but unfortunately, that IS the way it works. Until we as a whole demand that news be fact-checked at every stage (versus being regurgitated), and there are penalties involved, this cycle will never end.

I'm hoping it will finally get so retarded that we will demand it soon. It's already past that point for me (I don't even watch TV for news anymore, except comedy central).

If anything, they should have fact checked his article and said, "It's unlikely, but possible...". In which case there would be no sensational story, no attention, and therefore no change in the devices overall (except they will probably become less secure over time).

My brother, Steven Russell at Harvard Medical School, is a collaborator working on a bionic pancreas.

artificialpancreas.org

After I sent him a link to your post, he sent me the following link of a group that is studying these issues. It might be of interest.

secure-medicine.org

Timothy

The truth hurt, don't it

http://www.technologyreview.com/computing/38338/

"Personal Security

A wearable jamming technology could protect patients with implants from potentially life-threatening attacks."

You've used a Dexcom.

Come on, Scott,

There are really very few CGMs out there.

So when I see mention of a sensor with a watch battery that must last for two years, I know which CGM they are talking about.

But Scott, you just say, "Nope."

Marcus, you say, "Great analysis...."

Obviously Jay Radcliffe doesn't feel like explaining every little detail which could be resolved with a few seconds of investigation. I guess he doesn't want to spend the time and effort, and it's too bad.

It's too bad that this blog post is referenced by so many people.

It's too bad that this is supposed to be a technology blog by someone who knows something about diabetes and the products used to deal with it, yet it in this case it fails miserably in reviewing the technology and the implications to diabetics.

It's too bad that as bad as this post is, it may be at least one of the more accurate posts on the subject.

That's the internet, I guess.

I gave a very nasty reply, even worse than what I posted here earlier today. I apologize.

I still think (and verified by experiment) that this is information that could be obtained within seconds, but I don't have to be nasty.

We are talking about transmitters actually, and not sensors. In the case of both Medtronic CGM systems, the transmitter is rechargeable.

In the case of Dexcom, the transmitter uses a small, non-replaceable, watch-sized battery.

That's all of the CGMs on the market right now.

This was just one example of how things in this blog post which could have been investigated just weren't.

I apologize for making my point in obnoxious ways.

I still stand by my assertion that this is a tiny risk and that Jay may be overselling it.

Here is a reality check. No one who understands wireless in insulin pump operation would agree that you have "hacked" that pump. Here is my basis/definition: You are operating the device in ways specifically covered by the instructions for use.

By allowing this Black Hat presentation to get twisted out of control like a game of "telephone", your work may not yield the benefit you had hoped. Unless you can assert some control over the conversation, you put Medtronic and other vendors on the defensive of crisis management -- against a non-vulnerability -- so you can't as easily get the a dialog that starts between yourself and any of the vendors to learn more about how medical devices are designed.

This is the real loss. You would be pleasantly surprised (I say "surprised" based on your amateurish comments on designing around basic risks) that wireless penetration of these devices is considered in dozens of ways you have not pondered. The design procedures (and many of the people) come from aerospace backgrounds; but medical device design is a discipline of itself. The pump design teams that I have worked on are very aware that administering a deadly hormone for daily therapy is a very serious undertaking requiring painstaking risk analysis and mitigation.

I have not been directly involved with any of these companies in 3+ years but if this makes sense to you -- if you see some benefit to a richer dialog -- I would be happy to try to make/suggest some contacts.

<a href=http://www.theregister.co.uk/2011/10/27/fatal_insulin_pump_attack/" title="Insulin pump hack delivers fatal dosage over the air">http://www.theregister.co.uk/2011/10/27/fatal_insulin_pump_attack/</a>

I know this is quite an old post, but I am sure that this person could not hack just any device...

I am computer developer (I have diabetes management software, called Gnu Gluco Control (GGC)) and I have been trying to access device data (Minimed pump) for some time... While you can access device and read and set data or even boluses, you need to have serial number of the device... So yes this person could "hack" its own device, but not any other... And while he used term "hacked" any computer person would just say he accessed his device and set certain parameters.

While on one side, he is right, if you have sniffer, you can listen to device, on the other hand all data is encoded with your own serial number, which is needed for each command. Protocol is so bad, that it was hard to reproduce commands and any communication, until I took a look at original MM code for communication.

Problem with all diabetes devices is that each of them has its own protocol (language), so when someone want to support any device, he is limited to data, that company that created device provides him/her with or if sniffer is used... There were talks around several diabetes forums about using one protocol for all devices - standard (each device would then need to also use this common standard, which would give user just simple access to all measured data, for example each meter would implement commands for returning data, date and some basic needed info, without exposing any other commands to make changes to device)... But this will never happen...

Andy

Comments are closed.

Is it you on that picture? If so, you're really fit. However, something seems wrong... ;)

/Robert